First language acquisition is the study of how young children acquire their native language(s). This is a varied body of research and linguists do not agree on many of the details. However, it is clear that all children (no matter where they are born) pick up their native language according to the same basic timetable – regardless of whether or not parents correct their early mistakes. Even in the womb, a foetus prefers its mother’s language to any other foreign language. And, when they are born, children seem to know instinctively which sounds are simply noise and which carry information worth paying attention to.

Read more: Universal Grammar (UG)In short, young children appear to be predisposed to acquire language – and unravelling the mystery of this so-called problem of language acquisition is one of the biggest challenges in linguistics. The Universal Grammar (UG) hypothesis is a popular solution. In this article, I explain its background and main ideas.

1. The case for UG

Prior to the cognitive revolution in the 1960s, solutions to the problem of language acquisition were rooted in psychology – in particular, the behaviourist school of psychology associated with BF Skinner. The behaviourists thought that children acquired language simply by (i) imitating the sounds they heard around them, and (ii) responding to positive reinforcement. Clearly, there is some copying involved (e.g. children pick up bad words from the school playground). But this cannot be the full story, for a simple and logical reason.

Imagine that young children did acquire language by means of simple imitation. In this scenario, young children would have to hear every possible sentence structure and every use of each new word. Moreover, everything they heard would have to be grammatically correct – otherwise, they would reproduce the same errors. We know this does not happen. Parents often modify their speech when talking to infants (so-called baby-talk, or motherese). So it is very unlikely that young children are exposed to the full complexity and variation of their native language.

Adult native speakers will typically only use a subset of available sentence structures and available vocabulary. And even native speakers make occasional grammatical errors when tired or stressed. Speech can be grammatical and still suffer from non-fluency features such as hesitation, false starts and error correction. An infant acquiring language by imitation alone would also imitate these errors and non-fluency features. This is not what we observe.

2. The evidence

Newborns are accosted by all sorts of new sounds – and yet they somehow realize which of these sounds correspond to language. Even the linguistic input they do receive is incomplete and contains errors. But this does not stop infants around the world from acquiring the full range of sentence structures and morphological complexity in their native language. Any theory of language acquisition must take into account this so-called poverty of the stimulus issue.

It turns out that infants are able to intuit a lot about language. Consider the famous wug test, first carried out by Jean Berko Gleason in 1958. She showed children pictures of an imaginary creature called a wug and asked them to use the word in a variety of different sentence types. Children knew, even from a very young age, to add -s to denote the plural form. The design of the wug test makes it clear that children could not simply have memorized each word-formation rule individually. They had never heard of the word wug before, but they could intuit information about it. For example, the child participants knew that wug was a noun and they also knew which endings were associated with nouns.

Many linguists conclude from this that there is an abstract body of knowledge that underpins our language production.

3. The hypothesis

According to the Universal Grammar (UG) hypothesis, young children inherit (as part of their genetic endowment) a language module called Language Acquisition Device (LAD). Like other modules, LAD has two properties: (i) it is domain-specific, and (ii) it is semi-autonomous. It is domain-specific in the sense that the sole output of the language module is natural language. And it is semi-autonomous in the sense that it is kept separate from other regions of cognition (e.g. visual or auditory processing).

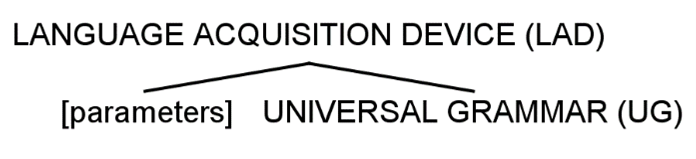

LAD contains two things: (i) Universal Grammar (UG), and (ii) a universal set of parameters. I have represented this in the diagram below.

(1) Partial schema for LAD

UG contains a universal set of computational operations. These operations are responsible for assembling words into phrases and sentences. The parameters define how the UG principles are expressed. Imagine each UG principle as a two-way switch. The parameter would determine which way to throw the switch. This event would have consequences for how the particular principle would be expressed in a language. UG refers to the initial state of child grammar: a child progresses from the initial state to adult-level competence by setting each parameter on the basis of the language they hear around them.

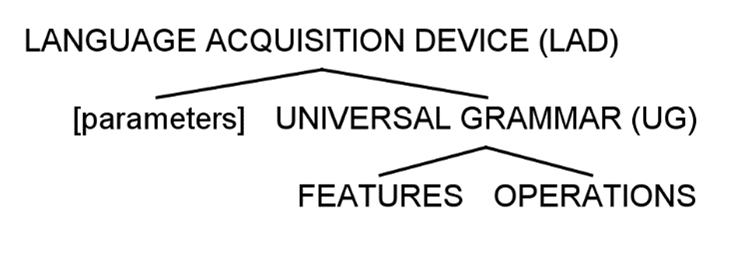

UG itself contains two things: (i) operations and (ii) features. I have represented this in the diagram below.

(4) Partial schema for LAD

Natural languages all exhibit the same set of core properties, but they do not all realize these properties in the same way. It is possible to deviate from a principle of UG within certain boundaries, as defined by the parameters. Consider Gender-marking on nouns. Languages often split up their nouns into a number of classes, which are distinguished by different morphological properties. French splits its nouns into two groups: masculine and feminine. But German adds a third distinction: neuter. Both French and German respect the Gender-marking principle, but they realize this principle in varied ways.

Young children do not have to discover the principles for themselves, but they do have to figure out which parameters are associated with each principle. Let us say that there is a binary choice for each principle. All languages have determiners (e.g. the) and nouns (e.g. ball) but the determiners can either be placed in front or behind the noun. In English, determiners always precede their nouns and children need to work this out. They achieve this by listening out for specific clues in their ambient linguistic environment. If they hear enough determiner phrases (e.g. the ball) they will deduce the correct setting of the parameter in question.

Think of UG as a toolkit for assembling a language. For example, there are many available phonemes but no single language has them all. English does not have click sounds and French does not have th. Rather, each language has a subset of available phonemes. The toolkit is the same but each language selects a different subset of phonemes. By hypothesis, language acquisition is now nothing but the setting of a finite number of parameters to their appropriate values. This approach to language acquisition is known as principles and parameters (P & P). It maintains that children set parameters on the clues found in their ambient linguistic input.

4. Summary

The Universal Grammar (UG) hypothesis arose as a response to the problem of language acquisition. In other words, it sets out to explain how every single child in the world learns his or her native language according to the same basic timescale, irrespective of parental input. The answer, according to advocates of UG, is that young children are biologically predisposed to acquire language.

Language Acquisition Device (LAD) contains two things: (i) Universal Grammar (UG) and (ii) a set of parameters. In turn, UG contains (i) a set of computational operations, and (ii) a set of features, which serve as inputs to these operations. All languages share the same general properties, although they realize these properties in different ways. For proponents of UG, the process of language acquisition essentially involves infants listening for clues in the linguistic input and setting parameters accordingly.